Month: February 2020

How to build a rocket workshop (part 5: the butchering)

This shed-to-workshop project is coming along well. So far, I’ve cleaned it out, added two new windows, replaced the old plywood doors with a nice new door (with a glass panel for even more natural light), and given a fresh coat of paint to the door frame and exterior shed walls. Not bad.

The next step is a less dramatic transformation, perhaps, but arguably one of the most important things for a future workshop: a proper work bench.

One of the main reasons I needed some sort of workshop in the first place was just for the additional space and work surface. Sure, it’d be great to have some simple power tools (table saw and vacuum for sawdust, drills, and so on) and other equipment, and a place to efficiently store all those tools. But my single biggest need is just for some extra space – a large work bench for projects, primarily building rockets.

I decided to go big with a butcher block countertop from Home Depot. In fact, they offer a few different sizes, and I went with the largest one they had, a full 96 inches (8 feet) in length. I found out two things about butcher block: it’s extremely heavy, and it’s expensive. But worth it!

After doing some initial research and arriving at a decision, I made the mistake of running up to the store myself and trying to purchase this alone. I could write a lengthy article just about the epic struggle of getting this thing off the shelf and hauling it to the front of the store, and loading it awkwardly into my small car (sticking partly out of an open trunk). I blocked many increasingly annoyed contractors in the store’s loading zone. I eventually managed to transport this thing home successfully, but at great cost to my pride, and my lower back.

The butcher block was unfinished wood, and this meant applying some sort of stain and/or seal to the wood, in order to protect it long-term. On a separate trip to the store, I picked up some simple clear wood stain, and also some clear polyurethane water based sealant, along with a couple of brushes.

As a side note, polyurethane can be either water based or oil based, and the difference is how they look after finishing the wood: water based is completely clear, while oil based will give the wood a soft amber look. It’s a purely aesthetic distinction and totally based on your own preference.

The staining and sealing process was nearly as epic as the journey from store to shed, though I didn’t realize this would be the case at first. Following the instructions provided on the can, at least two coats of the wood stain were necessary (to both the top and bottom of the butcher block, as well as all 4 sides), allowing ample time between coats to dry.

The polyurethane was even more demanding, requiring a minimum of three coats per surface. The fact that it took at least several hours for each coat to dry, and the sheer weight involved in trying to rotate this board, meant a multi-stage staining and sealing process that ultimately took more than a week.

This was also mid-winter and while Seattle winters are relatively mild, it was still cold enough to numb my hands halfway into the application of each new coat of stain and sealant. Several of those trips were done with light snow blowing into the shed, potentially ruining my otherwise perfect work.

Eventually, I finished preparing and protecting the board and mounted it along one wall inside the shed, centered under a window that provides plenty of natural light. Mission complete!

The only other major feature that a true workshop needs is electricity. And while digging a massive trench and running conduit and wire from my house out to the shed is an awful lot of work, it should also make a decent story, and a couple of good blog posts.

How to build a rocket workshop (part 4: painting)

I added a new step to my project that wasn’t in the original plan: painting. Gotta improvise sometimes.

With the old plywood doors removed and the new door and frame installed, the shed was looking much classier. But that part of the project required framing the new door properly, filling in new gaps with plywood, and caulking between the plywood sheets to seal it up. Basically, this left a bit of a mess, as you can see above.

In addition, the new door frame was just bare wood, without any paint or stain to cover and protect it. This would need to be painted not just for cosmetic reasons, but for longer term protection.

As for the rest of the shed, a new coat of paint will always clean things up. Besides, it had been a few years and was probably due for a new coat anyway. With nearly constant rainfall in the Seattle area all year round, exterior surfaces really take a beating from the weather.

The most difficult part of this phase wasn’t the painting at all – that was simple enough, and fun. It was trying to come as close as possible to matching the exact shade of blue here. To be fair, it didn’t need to match precisely, especially if I were going to re-paint the entire shed anyway. But our house was painted with the same color blue as well, and ideally the shed should continue to match the house.

So after half a dozen trips back and forth to Home Depot and a ridiculous number of paint chips, I was finally able to match the color. Much to my surprise, it’s not blue at all, but actually called “Sheffield Gray,” at least according to the paint’s official label.

The white paint for the door frame/ trim was a lot easier, and it didn’t matter quite as much whether it matched. I’m actually still torn about this color even after painting the frame because the house uses more of a gray color for the trim around all of the doors and windows. But hey, white looks nice too.

As mentioned above, the painting work itself is straightforward and actually fairly enjoyable. The exterior of the shed is not a particularly large surface area, and it’s not difficult to reach any area, so I didn’t even need a ladder or any tools other than a simple brush (and a screwdriver to pry open the paint can lid, and a hammer to shut it again).

If only the entire shed-to-workshop transformation project were this easy.

How to build a rocket electronics bay

I was originally going to create a series of articles dedicated to this topic: building an electronics bay for a rocket. Having never done this before, and having no idea what I was doing when I began, it took me quite a while to figure everything out and to actually build this thing.

In the end I decided nobody cares how long it took me to do this, and everyone is better off with a summary, even if it’s a slightly lengthy one. Quick table of contents based on the section titles below:

- Why am I here?

- What you’ll need

- More about the flight computer

- Step 1: Decisions and planning

- Step 2: Attaching the components

- Step 3: Dual deployment capabilities (optional)

- Final thoughts

Why am I here?

So to get started: I’ve covered in a few previous posts what an electronics bay (or “e-bay”) is, and why you might want to build one. Just to recap here, an e-bay is not strictly necessary to launch a rocket, but it lets you do a variety of cool things. For example, with the right electronics, you can measure and record exactly how high your rocket goes; fire charges to deploy one (or two!) parachutes with more precision during the flight; track its location after it disappears from sight and inexplicably lands far away; and much more.

But assuming you already know what an e-bay is and some of the cool things you can do with one, the next step is building it.

What you’ll need

There are a lot of different ways to go about doing this. A simple e-bay can have minimal components. For example:

- an altimeter to measure the rocket’s maximum height (it actually measures barometric pressure and uses that info to deduce the height);

- a battery; and

- an on/off switch.

That’s it, for the main components. In addition, you’ll need:

- copper wire to physically connect things together (if your switch doesn’t already come with wires); and

- some way to secure everything in place during flight (e.g. screws, or glue, etc.).

This last bullet can include nylon screws and washers (which I used for the flight computer), or just a lot of glue, or rubber bands or zip ties… you can get creative.

This simple e-bay wouldn’t have any ability to communicate wirelessly with things outside of the rocket, but it doesn’t need to. As long as you can locate your rocket post-flight and remove the e-bay and altimeter, it will provide you with useful data.

You can also go toward the other end of the spectrum and make the electronics as complicated as you want. But the basic concept is the same. You have at least one circuit board or flight computer, powered by at least one battery and connected to an on/off switch.

More about the flight computer

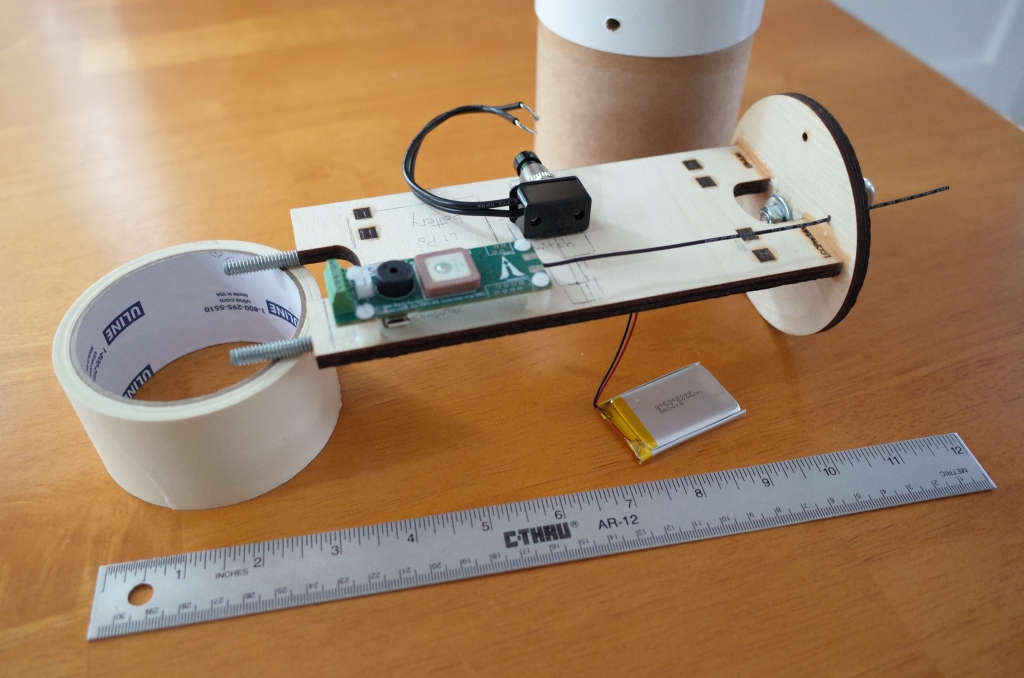

I chose to start with the TeleMetrum, which is a flight computer from Altus Metrum. It combines the functions of an altimeter with a few other abilities, including firing two separate pyro charges (for dual parachute deployment), GPS tracking, and a radio transmitter – hence the long antenna.

Physically, the TeleMetrum is just 1 inch wide by 2 3/4 inches long. It’s amazing how much cool tech can be crammed into such a small board. The antenna is 7 inches long, and ideally for this particular board you’d want an e-bay with at least 10 inches of interior length to accommodate the board and antenna. My e-bay was less than 8 inches, though, so I needed to extend the antenna somewhat outside of the actual e-bay. The antenna is flexible wire, but it’s best to keep it as straight as possible.

I’ve also previously posted about building the e-bay minus any of the electronics, so I’ll just skip ahead here, assuming you have already constructed an empty e-bay based on my spectacular instructions and are ready to add all of the fancy gadgets and components.

Step 1: Decisions and planning

As noted above, you’ll need to first decide exactly what you want in your e-bay. Do you just want a simple altimeter to measure height? Do you need to fire pyro charges to be able to do dual deployment? Do you want GPS tracking and radio communication with your rocket?

For my purposes, I wanted all of the above, which is why I selected the TeleMetrum after carefully reviewing the options.

I also got a rechargeable 900 mAh LiPo battery from Altus Metrum. It’s really small and lightweight. Finally, I got an unnecessarily large push-button on/off switch, and some 20 awg copper wire from Home Depot. As a side note, “awg” technically stands for American wire gauge, but this would typically be referred to as “twenty gauge wire.” Somewhat counter-intuitively, the larger the gauge number, the smaller or thinner the wire diameter. The one I bought, 20 awg, is sometimes called “bell wire” because it’s used for common household purposes that require small amounts of current, like doorbells or buzzers.

You can see from the pictures above how I placed the components in my e-bay. Simple, right? To be honest, I’d say at least 95 percent of this is just planning and understanding what you’re doing – making sure you have all the right parts, you understand how everything works together, and where exactly it will be placed. Once the planning is done, the rest is a piece of cake.

Step 2: Attaching the components

To attach the flight computer, which has pre-drilled holes right in the circuit board, I drilled 4 holes in the e-bay wooden “sled” and used 4 nylon screws. I also added a dab of epoxy to hold them in place, just in case. I’ve actually heard that nylon screws work really well for this purpose, because they will shear. If the rocket suffers a catastrophic failure or really rough landing, the impact may shear the nylon screws (which absorb most or all of the force), but preserve the flight computer intact. I don’t plan to test this out, but it can’t hurt.

The push-button switch I simply glued in place with epoxy. It’s important to note that you’ll also need to drill a small hole through the external wall of the e-bay, and that hole should line up with the switch. You should be able to push the button – and therefore arm or disarm your rocket’s flight computer and electronics – from outside the rocket by simply inserting a pencil, screwdriver, or other small thin object through the hole to push the button. Make sure the hole lines up with the switch!

Finally, to help secure both the switch and the battery in place, I cut a few very small pieces of wood and secured them using wood glue. This isn’t strictly necessary, but it helps give extra security to the switch, and keeps the battery from moving around. I also used a zip tie with the battery, which I can cut if I needed to remove or replace the battery – though that isn’t likely.

Depending on what kind of electronics you’ve chosen and/or what you want to do with your flight computer, you might be done at this point. If you just have a simple altimeter, or you aren’t interested in dual deployment (yet), you now have a finished e-bay. Congrats!

However, if you are interested in dual deployment, or you just enjoy exposing yourself to dangerous materials and explosions, read on.

Step 3: Dual deployment capabilities (optional)

For dual deployment, you’ll need – in addition to the above list – the following things:

- two small (1 inch) PVC pipe end caps;

- some small screws and matching washers;

- black powder (recommend FFFF); and

- electronic matches (“e-matches”) or electronic igniter, such as the MJG Firewire Initiator.

In addition, while not strictly necessary, you may find it helpful to also have:

- two 2-way barrier strips; and

- at least one 4-circuit male connector and one 4-circuit female connector.

You can see a white PVC pipe end cap and white two-way barrier strip in the photos above. One of each is attached on the outside of the e-bay, on each end, and they’re secured by drilling a hole, using a screw and washer, and also adding a few dabs of epoxy for good measure to hold everything in place.

The PVC pipe end cap will hold a small quantity of black powder, which will give you your explosive charge, separating the two parts of your rocket at the appropriate time and deploying your parachute. The black powder is ignited with the e-match, which is wired up to the flight computer (which tells it when to activate).

The reason for the barrier strip is to connect the e-match to the flight computer without having to disassemble everything every single time – it’s just more efficient to have permanent wires running from the flight computer to the barrier strip (which, again, is located on the outside of the e-bay for convenience), and to just be able to swap out the e-match more easily each time.

Similarly, the reason for the 4-circuit male and female connectors is just to more easily be able to pull your e-bay out and access things inside. With the connectors, you can simply disconnect the wire and pull things apart much more easily, and you can also use a shorter amount of total wire which takes up less space and doesn’t clutter up the inside as much.

Final thoughts

In this last picture, you can see the overall build of my e-bay. It’s nothing special to look at, but hey – it’s my first one. I also thought it was important to leave as much additional space as possible in case I want to add more electronics later, either for redundancy or to provide new capabilities for the rocket (GoPro camera anyone?). But your layout is up to you.

If all goes well, this whole setup will allow me to do much more in high power rocketry and accomplish a variety of goals I’ve set for myself in 2020.

A few final thoughts and some helpful tips:

- Plan. As mentioned above, most of the work here is just planning and understanding what you’re trying to do, and ensuring you have the right parts. Once you’ve solved for all of that, building is the easy part.

- Glue. When in doubt, use more wood glue or epoxy, not less. You can secure the components many different ways and have a lot of options.

- Layout. Leave room for additional future components (if you have the space for it). If not, no worries.

- Get creative. My antenna didn’t quite fit within the e-bay so I drilled a small hole to let it poke outside. And since it’s kind of close to explosive black powder, I shielded it with part of a plastic straw.

- Label everything. It’s good to sketch out what you’re trying to do ahead of time, and it’s also helpful to label parts as you go. You can see, for example, I wrote “TOP” with an arrow on the outside of the e-bay to make sure it’s inserted into the rocket body the right way. Once the e-bay is completely sealed up, it’s not always easy to remember which way is up!

Next up, I have some ground testing to do – before sending this thing thousands of feet into the air.

How to build a rocket workshop (part 3: the emergency exit)

You know what they say: when god closes one door, he opens another. Right?

I was googling to find the exact phrase (and its original source) and apparently one of the most popular google searches along these lines is “when god closes all doors.” If that happens, you should be very concerned. It’s definitely a bad sign.

For example, the room can suddenly erupt in a fiery inferno, and if god has closed all doors, how are you going to escape? You need an emergency exit. And if one doesn’t exist, you may need to build it yourself.

This, then, is the story of me building my own emergency exit to escape the inevitable fire and billowing black smoke that is sure to occur in the near future: aka, installing a door.

Our mundane garden shed came with what might generously be described as French doors. Generously would be the key word, here, because the doors are cheap, made of nothing other than thin plywood, and completely windowless. There’s no handle per se, but a nice metal padlock secures the structure from unwanted intrusion.

This phase of the shed-to-workshop project calls for the complete removal of these doors, and replacing them with a real door.

As with the windows, a lot of this is just measuring and planning. I considered putting in double doors (real non-plywood ones), but this is actually kind of a narrow space for that – the opening is only about 48 inches wide. On the other hand, that’s too wide for a single standard door, whose width is generally 36 inches. I decided to go with a single door and just put in a new wooden frame to accommodate it.

The height is also unusual here. A standard door would be approximately 78 to 80 inches in height, but the opening here with the plywood doors removed is only about 60 inches. Yes, that’s only five feet, meaning I have to duck to enter or exit, no matter what kind of door I use. It is a shed, after all.

In the end, I decided to get a fiberglass door, cut to a custom shorter height, with a large glass window to let in more natural light.

With the decisions made and planning complete, I placed an order for the door at a local shop, which includes the door jamb (i.e., the wooden part around the sides and top of the door). It arrived about a week later; in the meantime, I also picked up a heavy duty external locking door handle from Home Depot. As with the windows, I enlisted some help in removing the old plywood doors, framing and installing this new door.

But it’s finally done! You can see where the old plywood doors had been, and where their hinges had been attached. We were able to repurpose some of the plywood from the old doors to fill in the gap (since the new door is narrower), caulking to fill in the spaces.

Of course, this still needs some additional work to finish and clean it up. I’ll need to paint the entire front wall blue again, which will first require matching the exact shade of blue and buying the paint. And I’ll also need to paint the wood trim around the door, something like white or grey.

But cleaning up and painting is no big deal. The hard part is over, and the place has a nice new door! A proper emergency exit, which you can be sure I’ll use during an upcoming welding mishap or rocket engine explosion.

The workshop is coming along nicely. I think the next step will be to get a butcher block countertop and install that inside so I have a nice large workbench for rocket projects.

How to build a rocket workshop (part 2: the defenestration)

Defenestration (n). The act of throwing someone or something out of a window.

In particular, the Defenestration of Prague in 1618 involved some angry folks tossing several government officials out of a window from Prague Castle. Generally, when you have unwanted guests and you’d like them to leave, the preferred approach is to drop subtle hints that you need to wake up early the next morning, or start cleaning up. Maybe turn on a vacuum if they don’t get the hint. A forcible ejection through the window can have the immediate desired effect but may ultimately lead to a long and terrible war (in that case, the Thirty Years’ War).

Speaking of forcible ejections through the window, many things can go wrong when building or using a workshop, and I named each phase of my shed-to-workshop project after a small sample of them. In this “defenestration” phase, I’ll add windows to the shed.

First, I had to plan a bit: how many windows? And how large should they be? Of course, I want to maximize light, and my initial answers were more windows and bigger windows, respectively. But more windows cost more money and are significantly more work to install. And most importantly, there’s only so much room inside to actually use or store tools and equipment, and windows eat up some otherwise useful wall space.

Two windows seemed sufficient to really open up the space and provide ample natural light. I thought one on the side and one on the back wall made the most sense.

A shed would typically have pretty small windows, too, something like 12×24 inches or maybe 12×36. Larger would always be better, but then again, I didn’t want the windows to look ridiculously oversized on such a small structure. I ended up going with two windows that are each 24×48 inches.

The walls here are just simple plywood, so after the initial planning was done, this project required:

- measuring and cutting away the plywood rectangles where windows would go;

- cutting some wood and framing the window; and

- installing the window itself, along with some flashing.

Overall nothing too crazy, but a decent amount of work. I did have someone help me with this project; I’m ambitious but only mildly handy, and certainly not an expert.

And this is the finished product! It’s amazing how much a window or two can transform a room. It looks like a completely different space, flooded with light. It even feels bigger, and is the type of place I wouldn’t mind spending an afternoon working on a rocket build or some other project, especially in the spring and summer once the weather gets nicer.

On to the next step: replacing the plywood shed doors with a real door. Something to help class it up, maybe with some glass to add even more natural light. And a handle, ideally, to open and close this door. Maybe I’m going too far? One can always dream.

How to build a rocket workshop (part 1: the purging)

As I’ve mentioned before, I have an uninspiring simple garden shed in the back yard, and one of my goals for 2020 is to convert it into a workshop, primarily for rocket construction and related projects.

The shed is in good condition, though it’s only a small space, with an area of approximately 10×10 feet. It currently has crude plywood doors and a padlock, no windows or source of light, and it’s full of old junk, ranging from bulky A/C window units to a variety of leftover materials from the previous homeowners and contractors. Extra brooms, lumber, carpet, pipes, empty beer cans – you name it. There is also a layer of dust covering everything, seemingly several inches thick and whose only explanation can be a recent volcanic eruption nearby.

This is kind of a big project, so I’ve broken it down into a few major steps. Each of these has its own sub-steps, but I’ll spare you that level of excruciating detail and just leave it in my own personal to-do list. The major steps basically include:

- The Purging. Remove and haul away junk inside the shed, and clean it up.

- The Defenestration. Remove portions of walls, frame new windows, and install windows.

- The Emergency Exit. Remove old plywood doors, frame new door, and install door.

- The Butchering. Buy new butcher block countertop for a work surface, stain and seal it, and install.

- The Electrocution. Add electrical panel and wiring (running a line from the house) for light fixtures and outlets.

I’ll probably write a separate post for each of these steps, as I complete it. Starting with #1 here.

Long story short: I took some junk out of the shed and cleaned it up a bit. That’s it.

This is not particularly fascinating, but it’s kind of fundamental to completing the rest of the process, and to properly document this, I needed to start at the beginning. The previous owners of our house had hired some contractors to do quite a bit of renovation, and as mentioned above, they seem to have left a virtual treasure trove of useless junk in the shed. I got rid of as much as I could, though there’s still a bit left that I need to remove in order to complete the purge. Perhaps I’ll come across a rare antique, or a box full of cash.

But if nothing else, an empty clean shed is a blank canvas. It’s structurally sound, and it was built fairly recently and even has a new roof. Next I’ll add some natural light and really open it up.